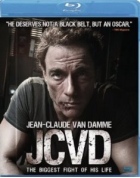

JCVD [Blu-Ray]

|

The opening shot of Mabrouk El Mechri's JCVD is an astonishing long take in which the camera tracks the eponymous action star Jean-Claude Van Damme as he does what we expect him to be doing: taking out bad guys with round-house kicks, rescuing a hostage, and leaving a lot of fiery explosions and bodies in his wake. It is one of many impressive long takes throughout this surprisingly impressive film, yet it is the only one that focuses entirely on violent action, which has been Van Damme's bread and butter since he first made a name for himself as the so-called "Muscles From Brussels" in 1988's low-budget Bloodsport. Yet, his career as an international martial-arts movie star has been on a steady decline into straight-to-video purgatory ever since it peaked in the early 1990s, which JCVD takes as its point of departure. Van Damme isn't playing one of his many fictional heroes, but rather a thinly fictionalized version of his decidedly antiheroic self, which may turn out to be his greatest role.

The opening shot of Mabrouk El Mechri's JCVD is an astonishing long take in which the camera tracks the eponymous action star Jean-Claude Van Damme as he does what we expect him to be doing: taking out bad guys with round-house kicks, rescuing a hostage, and leaving a lot of fiery explosions and bodies in his wake. It is one of many impressive long takes throughout this surprisingly impressive film, yet it is the only one that focuses entirely on violent action, which has been Van Damme's bread and butter since he first made a name for himself as the so-called "Muscles From Brussels" in 1988's low-budget Bloodsport. Yet, his career as an international martial-arts movie star has been on a steady decline into straight-to-video purgatory ever since it peaked in the early 1990s, which JCVD takes as its point of departure. Van Damme isn't playing one of his many fictional heroes, but rather a thinly fictionalized version of his decidedly antiheroic self, which may turn out to be his greatest role.

Written by director Mabrouk El Mechri and Frédéric Benudis, JCVD is a bold attempt to humanize Van Damme, not by trying to ignore his personal and professional pitfalls (which are many), but by reminding us that behind ever movie star, loved or loathed, is a complex human being who is constantly playing a role. The idea of making a movie in which Jean-Claude Van Damme plays himself as a washed-up loser sounds like a joke on paper, and while at times JCVD is quite funny, El Mechri (who is apparently a big Jean-Claude fan in real life) is going for something deeper and more profound, and he comes amazingly close to really nailing it. Along with other fellow B-level action icons like Steven Seagal and Chuck Norris, Van Damme has often been jeered for his wooden acting, but his performance in JCVD is nothing short of a revelation. Van Damme exposes a raw sense of exhaustion and frustration that transcends the surface meta-playfulness of having him play himself. Early in the film we see him in a Los Angeles courtroom where he is embroiled in a legal battle with his ex-wife for custody of his daughter (Saskia Flanders). Tired and frustrated, Van Damme must watch as the opposing lawyer berates the violent movies in which he stars, thus implying that he is a lousy father, but the truly painful moment is when his daughter takes the stand and tells of how her friends make fun of her whenever one of daddy's movies comes on TV. The comingling of hurt and shame on the actor's face frames the rest of the film's plot developments, elevating them from simple genre mechanics into a kind of redemption. The majority of the film takes place inside a post office in Van Damme's home town in Belgium, where the star goes to get a wire transfer to pay his lawyer, but instead becomes embroiled in a hostage crisis. At one point it appears that Van Damme is the ringleader of the standoff, which eventually involves the SWAT team, a sympathetic police negotiator (François Damiens), and throngs of people in the streets holding signs in support of their hometown star. El Mechri employs the tried-and-true approach of using multiple perspectives to lead us to one conclusion, and then reveal that something entirely different is going on, which keeps the hostage stand-off relatively tense while he cuts back to earlier scenes of Van Damme in his day-to-day life, talking with his agent about increasingly pathetic movie roles and dealing with jet lag and gabby cab drivers and fans who want to take their picture with him. Near the end of the film there is another particularly impressive long take, but one that differs substantially from the opening action setpiece. It is also centers on Van Damme, except this time it holds on him as he talks directly (or, more accurately, confesses) to the audience, explaining his views on life and his fears and his hopes and his mistakes and all of the other messy things that make him human. As he talks he inexplicably rises up and out of the scene at the post office until he is surrounded by set lights, a daring behind-the-curtains conceit that pulls us out of the fictional world of the movie and confronts us with the emotional nakedness of a star who has dropped all pretensions and stripped away all protective facades. It's a gripping moment in which Van Damme lets it all hang out, but in a way that is emotionally stirring rather than exploitative. And, even if it won't make any of his previous films play any better, it is certainly convincing in its suggestion that there is much more to the Muscles From Brussels than we ever expected.

Copyright ©2009 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Peace Arch Entertainment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Africa Leader news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Africa Leader.

More Information